The youtube sometimes cut the movie

Dorothy Dandridge Documentary Movie

Introducing Dorothy Dandridge (1999) [FULL MOVIE]

SURPRISED A LOT OF PEOPLE HAVEN'T SEEN THIS MOVIE, ENJOY.

The Life and Death of Dorothy Dandridge

Dorohty Dandridge was the first black woman to be nominated for an Oscar after her role in Carmen Jones.Dorothy had problems with depression threw out her life she committed suicide in 1962 at the age of 42

Dorothy Dandridge : Singing At Her Best

In this edition of the "In Concert" series, groundbreaking actress and chanteuse Dorothy Dandridge -- Hollywood's first black female star -- delivers an enchanting selection of timeless tunes.

Numbers include "Paper Doll," "Lazy Bones," "Swing for My Supper," "Cow Cow Boogie," "Blow Out the Candles," "My Heart Belongs to Daddy" and "You Do Something to Me." As a bonus, the video contains the documentary Dorothy Dandridge: An American Beauty.

by Deborah Latchison Mason, Contributing Writer

Dorothy Dandridge, acclaimed in her time to be one of the world's five most beautiful women, became one of Hollywood's most tragic victims.

Dandridge had everything it took to succeed in 1950s' Hollywood—she could sing, dance and act – except, she was born black. Though a product of the racially-biased era in which she lived, Dandridge rose to stardom to become both the first black woman to grace the cover of Life magazine and to receive an Academy Award nomination for Best Actress in a major motion picture.

Dates: November 9, 1922 -- September 8, 1965 Also known as: Dorothy Jean Dandridge

A Rough Start

When Dorothy Dandridge was born in Cleveland, Ohio on November 9, 1922, her parents were already separated. Dorothy’s mother, Ruby Dandridge, was five months pregnant when she had left her husband, Cyril, taking their older daughter Vivian with her.

Ruby, who did not get along with her mother-in-law, believed her husband was a spoiled Mama's boy who never intended to move Ruby and their children out of his mother’s house. So Ruby left and never looked back. Dorothy, however, regretted throughout her life never knowing her father.

Ruby moved into an apartment with her young daughters and did domestic work to support them. Additionally, Ruby satisfied her creativeness by singing and reciting poetry at local social events.

Both Dorothy and Vivian displayed a great talent for singing and dancing, leading an overjoyed Ruby to train them for the stage.

Dorothy was five years old when the sisters began performing at local theaters and churches.

After a short time, Ruby’s friend, Geneva Williams, came to live with them. (Family picture) Although Geneva enhanced the girls' performances by teaching them piano, she pushed the girls hard and often punished them.

Years later, Vivian and Dorothy would figure out that Geneva was their mother's lover. Once Geneva took over training the girls, Ruby never noticed how cruel Geneva was to them.

The two sisters' performance skills were exceptional. Ruby and Geneva labeled Dorothy and Vivian "The Wonder Children," hoping they would attract fame. Ruby and Geneva moved to Nashville with the Wonder Children, where Dorothy and Vivian were signed by the National Baptist Convention to tour churches throughout the South.

The Wonder Children proved successful, touring for three years. Bookings were regular and money was flowing in. However, Dorothy and Vivian had wearied of the act and the long hours spent practicing. The girls had no time for the usual activities youngsters enjoyed at their age.

Troubled Times, Lucky Finds

The onset of the Great Depression caused the bookings to dry up, so Ruby moved her family to Hollywood. Once in Hollywood, Dorothy and Vivian were enrolled in dancing classes at the Hooper Street School. Meanwhile, Ruby used her bubbly character to gain footing in the Hollywood community.

At the dancing school, Dorothy and Vivian made friends with Etta Jones, who had dancing lessons there also.

When Ruby heard the girls sing together, she felt the girls would make a great team.

Now known as "The Dandridge Sisters," the group's reputation grew. The girls received their first big break in 1935, appearing in the Paramount musical, The Big Broadcast of 1936. In 1937, the Dandridge Sisters had a bit part in the Marx Brothers' film, A Day at the Races.

In 1938, the trio appeared in the film Going Places, where they performed the song "Jeepers Creepers" with saxophonist Louis Armstrong. Also in 1938, the Dandridge Sisters received news they were booked for performances at the famed Cotton Club in New York City.

Geneva and the girls moved to New York, but Ruby had found success getting small acting jobs and thus stayed in Hollywood.

On the first day of rehearsals at the Cotton Club, Dorothy Dandridge met Harold Nicholas of the famous Nicholas Brothers dance team.

Dorothy, who was almost 16, had grown into a gorgeous young woman.

Harold Nicholas was mesmerized and he and Dorothy began dating.

The Dandridge Sisters were a huge hit at the Cotton Club and began to get many lucrative offers. Perhaps to get Dorothy away from Harold Nicholas, Geneva signed the group up for a European tour. The girls dazzled the sophisticated European audience, but the tour was shortened by the start of World War II.

The Dandridge Sisters returned to Hollywood where, as fate would have it, the Nicholas Brothers were filming. Dorothy resumed her romance with Harold.

The Dandridge Sisters performed in only a few more engagements and eventually split up, as Dorothy began to work seriously on a solo career.

Learning Hard Lessons

In the fall of 1940, Dorothy Dandridge had many favorable prospects. She wanted to succeed on her own—without the help of her mother or Geneva. Dandridge landed bit parts in low budget films, such as Four Shall Die (1940), Lady From Louisiana (1941), and Sundown (1941).

She sang and danced with the Nicholas Brothers to "Chattanooga Choo Choo” in the film Sun Valley Serenade (1941), along with the Glenn Miller Band.

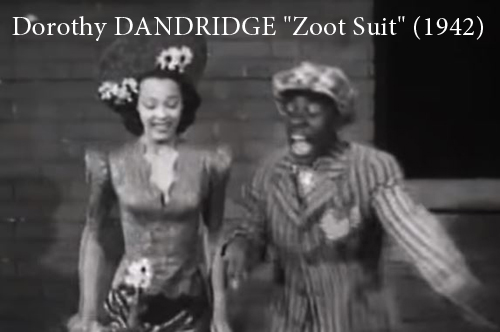

She sang and danced in the film zoot suit in 1942

Dandridge was desperate to be a bonafide actress and thus refused the demeaning roles offered to black actors in the 50s: being a savage, slave, or house servant.

During this time, Dandridge and Vivian worked steadily but separately—both longing to be free of Ruby's and Geneva's influence. But to truly pull away, both the girls got married in 1942.

A 19-year-old Dorothy Dandridge wed 21-year-old Harold Nicholas in his mother's home on September 6, 1942.

Prior to her marriage, Dandridge's life had been full of hard work and striving to please everyone. But now, all she wanted was to live contented being the ideal wife to her husband.

The couple bought a dream house near Harold's mother and entertained family and friends often. Harold's sister, Geraldine (Geri) Branton, became Dandridge's close friend and confidante.

Trouble in Paradise

All went well for awhile. Ruby wasn't there to exert control over Dandridge, and neither was Geneva. But trouble began when Harold began taking long trips away from home.

Then, even when home, his free time was spent on the golf course—and philandering.

As always, Dandridge blamed herself for Harold's infidelities—believing it was due to her sexual inexperience. And when she happily discovered she was pregnant, Dandridge felt Harold would be an adoring father and settle down at home.

Dandridge, 20, gave birth to a lovely daughter, Harolyn (Lynn) Suzanne Dandridge, on September 2, 1943. Dandridge continued to gain small parts in films and was a very doting, loving mother to her daughter. But as Lynn grew, Dandridge sensed that something was wrong.

Her hyper two-year-old cried consistently, yet Lynn was not speaking and did not interact with people.

Dandridge took Lynn to many doctors, but none could agree on what exactly was wrong with her. Lynn was deemed permanently retarded, likely due to a lack of oxygen during birth.

Again, Dandridge blamed herself, as she had tried to delay delivery until her husband arrived at the hospital. During this troublesome period, Harold was often physically and emotionally unavailable to Dandridge.

With a brain-damaged child, nagging guilt, and a crumbling marriage, Dandridge sought psychiatric help that led to a dependence on prescription drugs. By 1949, fed up with her absentee husband, Dandridge obtained a divorce; however, Harold avoided paying child support.

Now a single parent with a child to raise, Dandridge reached out to Ruby and Geneva who agreed to care for Lynn until Dandridge could stabilize her career.

Working the Club Scene

Dandridge loathed doing nightclub acts. She hated wearing revealing clothing, as the eyes of wanton men strolled over her body. But Dandridge knew that obtaining a substantial movie role immediately was impossible and she had bills to pay. So to add polish to her skills, Dandridge contacted Phil Moore, an arranger she worked with during her Cotton Club days.

With Phil's help, Dandridge was reborn as a sultry, sexy performer that dazzled audiences.

They took her act throughout the United States and were mostly well received.

However, in places like Las Vegas, the racism was just as bad as in the Deep South.

Being black meant that she could not use the same bathroom, hotel lobby, elevator, or swimming pool as white patrons or fellow actors. Dandridge was “forbidden” to speak to the audience.

And despite being the headliner at many of the clubs, Dandridge's dressing room was usually a janitor's closet or a dingy storage room.

Am I a Star Yet?!

Critics raved about Dorothy Dandridge's nightclub performances. She opened at the famed Mocambo Club in Hollywood, a favorite meeting place for many movie stars.

Dandridge was booked for shows in New York and became the first African American to stay in and perform at the elaborate Waldorf Astoria.

She moved into the Empire Room of the famed hotel for a seven-week engagement.

Her club performances gave Dandridge much-needed publicity to get film work in Hollywood.

The bit parts began to flow in but to get back on the big screen, Dandridge had to compromise her standards, agreeing in 1950 to play a jungle queen in Tarzan’s Peril.

The tension between making a living and defending her ethnicity would shape the rest of her career.

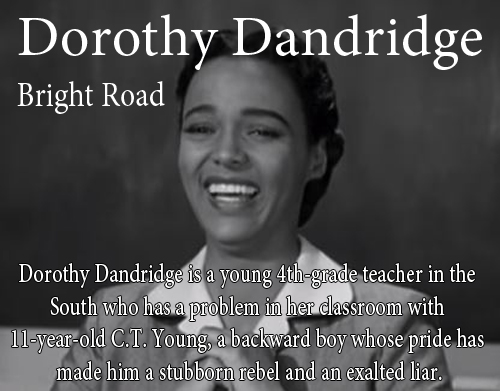

Finally, in August 1952, Dandridge got the kind of role she longed for as the lead in MGM's Bright Road, an all-black production based on a schoolteacher's life in the South.

Dandridge was ecstatic about the major role and it would be the first of three films played with her handsome co-star, Harry Belafonte. They would become very close friends.

Bright Road was very fulfilling for Dandridge and the good reviews were about to reward her with the role she had waited for all her life.

At Last, A Star

The lead character in the 1954 movie Carmen Jones, based on the famous opera Carmen, called for a sultry vixen. Dorothy Dandridge was neither, according to friends closest to her.

Ever the sophisticate, it was reportedly thought by the film's director, Otto Preminger, that Dandridge was too classy to play the indelicate Carmen.

Dandridge was determined to change his mind. She found an old wig at Max Factor's studio, a low-cut blouse and wore it off the shoulder, and a seductive skirt.

She arranged her hair in tousled curls and applied heavy make-up.

When Dandridge rushed into Preminger's office the next day, he reportedly yelled, "It's Carmen!"

Carmen Jones opened on October 28, 1954 and was a smashing success. Dandridge's unforgettable performance earned her the privilege of being the first black woman to grace the cover of Life magazine. But nothing could compare to the joy Dandridge felt upon learning of her Academy Award nomination for Best Actress.

No other African American had earned such a distinction.

After 30 years in show business, Dorothy Dandridge was finally a star.

At the Academy Award ceremony on March 30, 1955, Dandridge shared the Best Actress nomination with such major stars as Grace Kelly, Audrey Hepburn, Jane Wyman, and Judy Garland. Though the award went to Grace Kelly for her role in The Country Girl, Dorothy Dandridge became etched in the hearts of her fans as a true heroine.

At the age of 32, she had broken through Hollywood's glass ceiling, winning the respect of her peers.

Tough Decisions

Dandridge's Academy-Award nomination catapulted her to a new level of celebrity. However, Dandridge was distracted from her new-found fame by troubles in her personal life.

Dandridge’s daughter, Lynn, was never far from mind—now being cared for by a family friend.

Also, during the filming of Carmen Jones, Dandridge began an intense love affair with her separated-but-still-married director, Otto Preminger. In 50s America, interracial romance was taboo and Preminger was careful in public to show only a business interest in Dandridge.

In 1956, a huge movie offer came—Dandridge was offered the supporting-actress role in the major film production, The King and I. However, upon consulting Preminger, he advised her not to take the role of the slave girl, Tuptim. Dandridge ultimately turned down the role but would later regret her decision; The King and I was an enormous success.

Soon, Dandridge's relationship with Otto Preminger began to sour.

She was 35 and pregnant but he refused to get a divorce. When a frustrated Dandridge presented an ultimatum, Preminger broke off the relationship. She had an abortion to avoid scandal.

Afterwards, Dorothy Dandridge was seen with many of her white co-stars. Anger over Dandridge dating “out of her race” was incited by the media. In 1957, a tabloid ran a story about a tryst between Dandridge and a bartender at Lake Tahoe.

Dandridge, fed up with all the lies, testified in court that the caper was impossible, as she was confined to chambers due to an enforced curfew for people of color in that state.

She sued Hollywood Confidential's owners and was awarded a $10,000 court settlement.

Bad Choices

Two years after the making of Carmen Jones, Dandridge was finally in front of a movie camera again. In 1957, Fox cast her in the film Island in the Sun alongside previous co-star Harry Bellafonte.

The movie was highly controversial as it dealt with multiple interracial relationships.

Dandridge protested the dispassionate love scene with her white co-star, but the producers had been afraid to go too far. The film was successful but was deemed nonessential by critics.

Dandridge was frustrated. She was smart, had looks and talent but could not find the right opportunity to showcase those qualities as she had in Carmen Jones. It was clear that her career had lost momentum.

So while the United States pondered its race issues, manager Earl Mills secured a movie deal for Dandridge in France (Tamango). The movie portrayed Dandridge in some steamy love scenes with her blond-haired co-star, Curd Jurgens.

It was a hit in Europe, but the film was not shown in America until four years later.

In 1958, Dandridge was chosen to play a native girl in the film, The Decks Ran Red, at a salary of $75,000. This film and Tamango were considered unremarkable and Dandridge grew desperate at the lack of suitable roles.

That’s why when Dandridge was offered the lead in the major production Porgy and Bess in 1959, she jumped at the role when perhaps she should have refused it.

The characters of the play were the very stereotypes—drunks, drug addicts, rapists and other undesirables—Dandridge had avoided her entire Hollywood career.

Yet she was tormented by her refusal to play the slave girl Tuptim in the The King and I.

Against the advice of her good friend Harry Belafonte, who refused the role of Porgy, Dandridge accepted the role of Bess. Even though Dandridge's performance ranked high, winning a Golden Globe Award, the film failed utterly at living up to the hype.

Dandridge Hits Bottom

Dorothy Dandridge's life fell apart completely with her marriage to Jack Denison, a restaurant owner. Dandridge, 36, loved the attention Denison lavished upon her and wed him on June 22, 1959. (Picture) On their honeymoon, Denison mentioned to his new bride that he was about to lose his restaurant.

Dandridge agreed to perform at her husband's small restaurant to attract more business.

Earl Mills, now her former manager, tried to convince Dandridge that it was a mistake for a star of her caliber to perform at a small restaurant. But Dandridge listened to Denison, who took over her career and isolated her from friends.

Dandridge soon discovered that Denison was bad news and only wanted her money.

He was abusive and often beat her. Adding insult to injury, an oil investment that Dandridge bought into turned out to be a huge scam.

Between losing the money her husband had stolen and the bad investment, Dandridge was broke.

Around this time, Dandridge began drinking heavily while taking anti-depressants. Finally fed up with Denison, she kicked him out of her Hollywood Hills home and filed divorce papers in November 1962.

Dandridge, now 40, who earned $250,000 in the year she wed Denison, returned to court to file for bankruptcy. Dandridge lost her Hollywood home, her cars—everything.

Dorothy Dandridge hoped her life would now take an upswing, but not so. In addition to filing for divorce and bankruptcy, Dandridge was again caring for Lynn—now 20 years old, violent, and unmanageable.

Helen Calhoun, who had been caring for Lynn over the years and being paid a substantial weekly salary, returned Lynn when Dandridge missed paying her for two months.

No longer able to afford private care for her daughter, Dandridge was forced to commit Lynn to the state mental hospital.

A Comeback

Desperate, broke, and addicted, Dandridge contacted Earl Mills who agreed to again manage her career.

Mills also worked with Dandridge, who had gained a lot of weight and was still drinking heavily, to help her regain her health. He got Dandridge to attend a health spa in Mexico and planned a series of nightclub engagements for her there.

By most accounts, Dorothy Dandridge was coming back strong.

She received a very enthusiastic response after each of her performances in Mexico.

Dandridge was scheduled for a New York engagement but fractured her foot on a flight of stairs while still in Mexico.

%20-%20The%20Man%20I%20Love.JPG)

Before she did more traveling, the doctor recommended having a cast placed on her foot.

Beautiful Dorothy Dandridge introduces MLK

The End for Dorothy Dandridge

On the morning of September 8, 1965, Earl Mills called Dandridge regarding her appointment to apply the cast. She asked if he could reschedule the appointment so she could get more sleep.

Mills got the later appointment and swung by to get Dandridge in the early afternoon.

After knocking and ringing the doorbell with no response, Mills used the key Dandridge had given him, but the door was chained from the inside.

He pried open the door and found Dandridge curled up on the bathroom floor, head resting on her hands, and wearing only a blue scarf. Dorothy Dandridge was dead at the age of 42.

Her death was initially attributed to a blood clot due to her fractured foot. But an autopsy revealed a lethal dose—over four times the maximum therapeutic dosage—of the anti-depressant, Tofranil, in Dandridge's body.

Whether the overdose was accidental or intentional is still unknown.

According to Dandridge's last wishes, which were left in a note and given to Earl Mills months before her death, all her belongings were given to her mother, Ruby. Dorothy Dandridge was cremated and her ashes interred at the Forest Lawn Cemetery in Los Angeles.

For all her hard-working, extensive career there was only $2.14 left in her bank account to show for it at the end.